As criminal online fraudsters rapidly diversify their revenue streams, policy abuse is quickly gaining attention — both by those who commit fraud and by those who seek to prevent it. The true cost of policy abuse is the most alarming of all and is usually vastly underestimated by those most effected by it.

What is policy abuse?

Policy abuse is something of a catch-all for malicious attacks on ecommerce brands that bypass traditional payment fraud and instead rely on loopholes in merchants’ policies and vulnerabilities in their procedures. Examples of policy abuse, including promotion abuse, unauthorized reselling and return fraud are on the rise as merchants and fraud-protection providers get better at turning away fraudulent orders at checkout.

For an idea of how fraud and abuse beyond payment fraud is on the rise, it’s instructive to look at the elements of first-party fraud and abuse that are measurable — namely scams that produce chargebacks, such as false claims of missed deliveries or false claims of receiving unsatisfactory products.

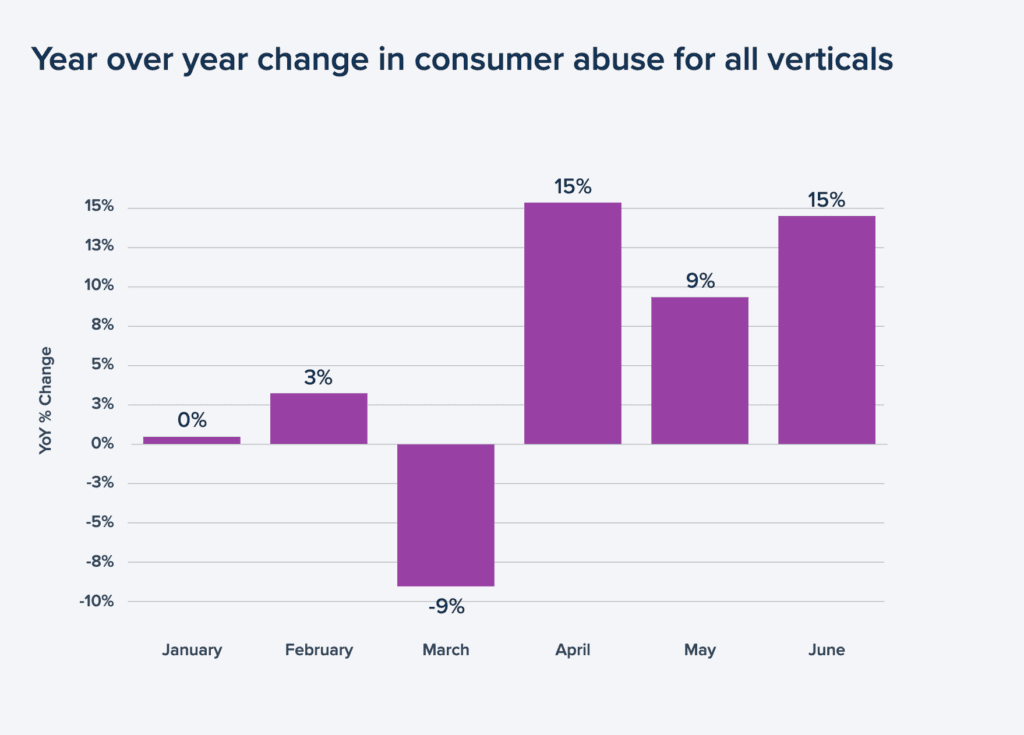

In the first half of 2024, those forms of consumer abuse were consistently higher than during the first half of 2023. While consumer abuse ended the first six months of the year up 4%, the increase accelerated dramatically in the second quarter. Broken down by month, consumer abuse was up 15% in April, 9% in May and 15% in June on an annual basis, according to Signifyd data.

And while policy abuse scams take many forms, recently two rising stars have been emerging in the category — promo abuse and reseller abuse.

What is promo abuse?

Promo abuse involves unscrupulous behavior such as using a one-time-only discount code several times, creating a web of email accounts in order to refer “friends” to a site or product in return for a discount, or simply stacking discounts upon each other in violation of the terms of the deal.

Another growing variation of the promo problem involves introductory subscriptions or free trials. By creating multiple accounts — sometimes on a massive scale — criminal rings can stockpile free or cut-rate access to all sorts of resources and services and sell them on the dark web or even on the brightly lit web.

Subscription fraud is one of the many forms of policy abuse

Adobe’s Prerit Uppal says subscription fraud is a thing. Determined fraudsters take advantage of policies to encourage sign-ups in a number of different ways. Here’s a quick explanation by Adobe’s group product manager payments and risk.

Promo abuse is the sort of indiscretion that might seem almost innocent when pulled off by a wayward consumer on a small scale. But consider the advancements in AI now deployed by criminal fraud rings and the ability to create hundreds of accounts or more in a matter of hours or less.

The rise of bots in the fraud and abuse world means relatively small wins — a free trial, a discount code, a reward for recruiting a new customer — can become lucrative at scale. Fraud rings can create hundreds or thousands of accounts to take advantage of first-time-buyer promotions or referral rewards.

How does promo abuse enable other forms of policy abuse?

Promo abuse can be a gateway to other forms of abuse, says Signifyd Senior Manager, Risk Intelligence Xavi Sheikrojan. For instance, he says, fraud rings bent on reseller abuse will use multiple promo codes to clear out the inventory of a highly desirable product at a discounted price. They will then resell the coveted items on a marketplace at a big markup, made all the more profitable because they were purchased at a sale price.

Or a fraud ring will use discounts to purchase high-value items that become the basis for return fraud schemes. The ring will return a knock-off or something other than the original product for a quick or instant refund. Buying at an exaggerated discount by stacking discount codes or using “one-time” offers on multiple purchases reduces the initial investment a ring must make to commit fraud.

What is reseller abuse?

The rise of bots is also powering the second growing form of policy abuse — reseller abuse. As bots have become cheaper, more efficient and easier to program, industrialized reselling operations have turned to rapid-fire buying to corner the market on scarce and desirable items. Fraudsters also look to turn shopping bots on products that they can arbitrage by taking advantage of promotions and sales or benefiting from regional price differences. In other words, unauthorized resellers buy low and sell high — often on marketplaces.

At first blush, unauthorized reselling is a puzzling problem. After all, doesn’t an online merchant that falls victim to unauthorized reselling actually make a sale? Lots of sales, in fact? Well, yes, but in the process, a litany of problems arise. We’ll get into that later as we explore the hidden cost of policy abuse.

How much is policy abuse costing merchants in 2024?

The full cost of policy abuse is difficult to quantify precisely. Definitions are fuzzy. Different terms are used interchangeably and they are used to mean different things in different contexts — friendly fraud, first-party fraud, first-party abuse, consumer abuse.

The National Retail Federation for years has reported on the scope and cost of return abuse online — nearly 11% of ecommerce returns in 2022 were fraudulent, for instance, costing retailers $22.8 billion. (For 2023, the NRF reported only an overall return rate for online and in-store, which was 13.7%.) But unlike payment fraud and false claims about missing packages or damaged goods that result in a chargeback, a growing list of first-party abuse types defy precise accounting.

In fact, a significant number of merchants either may not realize they have a promo abuse problem — or at least they may not realize the extent of it. Reseller abuse is easier to identify, but the costs of the crime often lie in opportunities and customer loyalty lost.

There is a cost. That’s undeniable. Consider promo abuse. The idea of offering a promotion is often to attract new customers — here’s a discount on your first purchase; here’s a discount on an upcoming purchase if you send us a new customer. Oh, and by the way, that new customer will get a discount, too.

“New” customer promos are being abused

Now consider the result when bad actors create hundreds or thousands of email accounts in order to appear as new customers or as customers referred to the merchant by another customer. In those cases, a merchant is spending a lot of money and the only customer they’re attracting is a fraudster taking advantage on a large scale.

To get an idea of the potential for damage from promo abuse, you need only look at a few notorious examples. There was the 20-something who amassed $50,000 in Uber credits via referral rewards. Uber eventually got wise.

And then there was PayPal’s misfortune with a promotion aimed at encouraging new customers to open PayPal accounts. PayPal would pay each new account owner $10 just for signing up. The payments platform ended up closing 3.5 million accounts that it determined had been created by bad actors. The arithmetic — $35 million — is not pretty.

The PayPal case is a cautionary tale that Karisse Hendrick, host of the Fraudology podcast, pointed to during a Merchant Risk Council webinar examining the shifting trends in first-party fraud.

During the webinar, Hendrick noted that the vulnerabilities that make promo abuse a successful scam derive from the fact that unlike payment fraud and false claims that result in chargebacks, promo abuse has not typically been on risk teams’ radar.

Promotions are generally planned and launched by the marketing department. Depending on the retailer, fraud and risk teams might not even be aware a promotion is underway. Add to that, that organized criminal rings are constantly expanding their targets and you have the ingredients for a growing challenge.

“This is scalable,” Hendrick said during the webinar. “This is with hostile fraudsters. They are taking this approach. They are trying to look like your good customers.”

What are the hidden costs of policy abuse?

Hidden costs of promo abuse:

Beyond the initial financial hit, policy abuse brings long-lasting costs that cannot be recovered. For instance, promo abuse obviously results in shrinking profit margins on each sale.

But that’s just for starters. It also:

- Scrambles the data that marketing teams use to evaluate the success of a given promotion. By some metrics, a promotion might look to be a huge success given the number of customers who took advantage of discount codes. Unless, of course, that large number of consumers actually consisted of one fraudster or a group of fraudsters.

- Irritates customers who play by the rules. Word gets around — through social media for instance — that some customers are getting a deal they don’t deserve.

- Feeds on itself. When word spreads that a given online brand is an easy mark for promo abuse, the devious crowd rushes in. And word will spread.

Hidden costs of reseller abuse:

The financial damage that reseller abuse causes is not always obvious. As we pointed out, in most cases the victimized retailer actually makes a sale. Always good to move inventory, right? Well, no.

How unauthorized reselling kills customer experience

Devanshu Agarwal has seen the damage that unauthorized reselling can do to the thoughtfully crafted relationship between merchant and customer. Agarwal is the direct-to-consumer payment risk manager for sportswear brand On. Watch the brief video to hear how resellers can shread the bond that brands build.

First of all, the sale is not always legitimate. It’s not unheard of for criminal rings to use stolen financials along with automation to make large-scale purchases of items with profit potential on secondary markets.

But even in cases when legitimate payment methods are used, the high-volume sales come at a steep cost. When a reseller corners the market on a product and sells it off on a marketplace:

- Legitimate customers are disappointed when they’re unable to buy a sought-after product from a retailer they know and trust.

- Consumer frustration could be further aggravated when landing the coveted item means paying a premium to a reseller out to make a healthy profit.

- The original merchant misses out on valuable customer data. It’s the marketplace and unauthorized reseller that have the opportunity to establish a relationship when a customer makes a purchase.

- Online D-to-C brands lose control of the customer experience. The brand has no way to ensure fulfillment is fast and seamless. The brand loses the connection needed to answer questions from the consumer about the product or how to operate the product.

- Online merchants also lose the possibility for upselling or cross-selling.

How can merchants detect policy abuse and prevent it?

While a portion of policy abuse is committed by bad actors intent on taking advantage of retail practices meant to make shopping easier and more enjoyable for good customers, another portion arises when good customers become frustrated or feel they’ve been treated unfairly. Merchants can avoid cases where a customer is using policy abuse to exact their own brand of retail justice by:

- Being obsessively transparent. Clearly detail your policies on your website, including rules for returns, using discount codes, delivery times and refund expectations.

- Being proactive when things go wrong. Texts, emails and frequent communication go a long way to ease the stress of the unknown.

- Be available through email, online chat and call centers to deal with any customer concerns or questions.

After all, it’s harder to cheat someone you know and someone who’s treated you well, so treat your customers well.

For the tough cases, the cases in which a criminal organization or even a mendacious customer is intent on taking advantage, there are additional steps merchants should consider.

- Carefully monitor transactions related to promotions and discounts. If you detect an unusually large surge in such orders, dig in and determine whether a deliberate attack is underway.

- Rely on device-ID monitoring to determine whether multiple discounted orders are being placed on the same device or related devices.

- Watch for unusually high velocity around orders including promotional discounts.

- Introduce checkout steps that deter bot attacks, such as step-ups or captcha requirements. Of course, these sorts of solutions add friction that could lead legitimate customers to abandon their orders.

- Turn to a consortium strategy by pooling transaction data with other merchants to identify customers who have a history of violating promotions or policies covering reselling or returns.

While building a consortium model would take a concerted effort to coordinate among a group of retailers, it provides the key element in detecting and preventing policy abuse: Understanding the identity and intent behind every transaction. Signifyd customers already have such protection available.

Signifyd’s Decision Center identifies and turns back policy abuse by tapping into the vast intelligence generated by the company’s Commerce Network of thousands of online retailers. The scale of the network means that Signifyd has previously seen elements of 98% of the transactions executed on its network.

Decision Center’s insights allow merchants to identify serial abusers and resellers and block illegitimate requests and transactions. The technology allows merchants to calibrate the response to promotion use, refund requests and reseller activity depending on the degree of risk each transaction presents.

It is the sort of innovation that those working to push back on the growing threat of policy abuse will continue to work on and improve — just as those looking to take advantage continue to evolve and seek out new targets.

Feature photo by Getty Images

Looking to tame policy abuse? We can help.